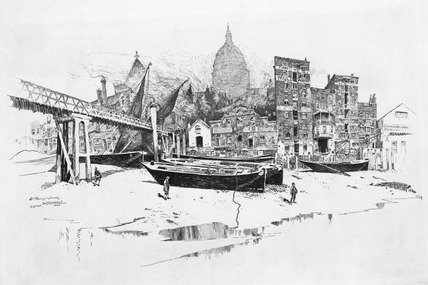

Paul’s Wharf by Joseph Pennell (1884)

Very many of the crimes prosecuted at the police courts were easily dealt with by the magistracy who handed down fines or short spells of imprisonment. However, the courts also acted as filters for the jury courts – the Middlesex sessions and Central Criminal court at Old Bailey. When a very serious case – like today’s – came before the justices their task was to stage a pre-trial hearing and commit the defendant to take his trial later.

Samuel William Liversedge was a commercial traveller. The 33 year-old worked for a City jewelers based at 44 St. Paul’s Churchyard, Goddard & Lawson. He enjoyed the full confidence of his bosses, being trusted with thousands of pounds worth of jewelry each week, which he took around the various shops in the capital to sell. He was paid on commission but with a retaining salary, and this was always topped up to 50s a week so Samuel was well remunerated for his work.

At some point in 1877 things began to wrong for him it seems. Whether he simply succumbed to the temptation that carrying around a small fortune in precious stones and gold and silver presented, or perhaps because he was in debt despite his generous salary. Either way as early as April that year he began to steal from the firm.

Things came to a head in November when Liversedge left St. Paul’s Churchyard with £1,000 worth of items in his usual black leather bag. When he got back, that evening, he was excitable and somewhat the worse for drink. The bag was missing and he told his Mr Goddard and Mr Lawson that he’d been robbed on a train whilst traveling between Edgware Road and King’s Cross. By his account he’d entered a carriage in which there were three men and a woman and as they left they brushed past him and must have pinched the bag containing all the jewelry. He called the guard who was unable to stop the train and so the thieves got away.

That was his story but it didn’t hold up in court, either at the Guildhall (before Sir Andrew Lusk) or later at the Old Bailey in March 1878. The guard testified at Liversedge’s trial and said he had looked for the three men and a woman and had seen no one leave his train carrying a bag such as had been described.

The bag did reappear at about 6.30 the same evening, ‘floating off Paul’s Pier, with the empty jewel cases and the cards attached to them’. William Barham found them. Barham was a Thames lighterman and he saw the bag in the water and fished it out. Lightermen knew the river intimately and was sure that it hadn’t been in the water long. The bag was closed and there was hardly any water inside, so someone had thrown it in not long before.

Goddard and Lawson had taken a cab to Scotland Yard as soon as their traveler had told them he’d been robbed. They had been told to make a full inventory of the missing items and came back to tell Liversedge. He suggested they all go to Bow Lane police station to do this, which they objected to. Samuel ignored them and rushed off to the station where he gave a list of the missing items, but a very short and partial one. Crucially Bow Lane Police station was close by Paul’s Wharf, where the bag was later found.

Sir Andrew Lusk heard from the prosecutors that at first they’d wanted to deal with this carefully and without prejudicing any future court case. Fundamentally they wanted their goods back though and hoped that some publicity might lead to the identification of items that they expected that LIversedge had pawned. They asked for a remand which the magistrate granted.

It took a while for this to all reach the Central Criminal Court but in March of the following year Samuel Liversedge was formally tried and convicted of stealing ‘three watches, one pendant, nine pairs of earrings, and other articles’ belong to the City firm. Several pawnbrokers turned up to give evidence that they had received items from Liversedge over the course of the last six months or so. The jury found him guilty and the judge sent him to prison for seven years at penal servitude.

Whatever motivated Liversedge to steal from his masters and jeopardize a pretty well paid career is a mystery; his voice – if he spoke at all – is not recorded in the Old Bailey Proceedings and we don’t know what happened to him thereafter. At 33 he was probably fit enough to survive 5 or so years in gaol before he earned his ticket of leave but his chances of returning to that level of trusted employment were slim.

[from The Standard, Monday, December 10, 1877]

An intriguing case. I am left really wondering what induced this man to ruin his life like that.

LikeLike