A veteran of the Crimean War

Whilst today is Hallo’een and this evening we will be inundated with small children flying high on sugar and commercialized excitement this is also the week that poppy sellers really began to make an appearance. I’m not going to engage in the debate as to whether or not anyone should wear a poppy (or what colour that poppy should be); I believe that men and women have died in wars to preserve our freedoms and the freedom to wear a poppy (or not) is part and parcel of that.

Poppies were first sold in Britain in 1921, the year the Royal British Legion was formed. It sold 9,000,00 of them and raised £106,000 for veterans from the First World War. Last year 40,000,000 were sold worldwide and now the Legion helps veterans from all wars in the 20th and 21st century. The FWW was meant to be the ‘war to end all wars’, sadly it wasn’t.

What struck me about the reportage from the London Police courts for hallo’ween 1870 was a story about six young lads who had been collecting money for veterans, just as the Legion’s poppy sellers do today. The boys (part of a wider group of 36 they said) had approached Sir Robert Carden at the Guildhall just as the court was closing for the day.

A spokesman for the group piped up to say that they were asking for the magistrate’s help as they hadn’t been paid. When asked they said they took a stand in the street and collected money in a box which they then returned to the clerks in ‘the office’. Depending on the amount they raised they were paid between 2s6dand 4sa week. However, when they went to collect their money that day the office was closed and they had gone away empty handed.

It seems they were collecting considerable sums of money from the public. They knew how much because the opening used to remove cash was kept sealed. Nevertheless the boys could feel the weight of the boxes and could see the money being put in them. One lad, who stood outside Bow Church on Cheapside said that he seen a gentleman put in a sovereign and two other men donate half sovereigns. Each box must have amounted to a considerable sum and so for just a few shillings a week the lads were doing great work in drumming up money for the charity.

Sir Richard was sympathetic to their plight but thought that it might just be a temporary error on the behalf of the clerks to forget to pay these six individuals. He advised them to try once more the next day but to return to see him they remained unpaid. In that case, he said, he would take more formal action against the charity.

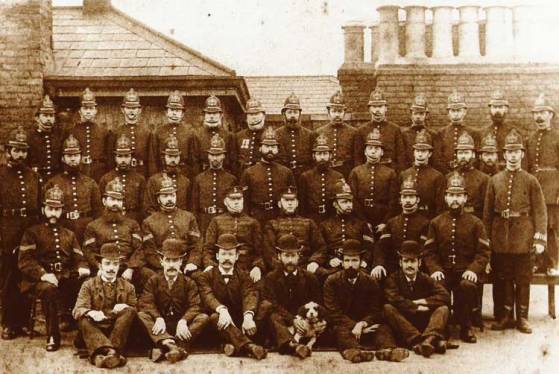

So this shows us that the courts were used for more than just crime, they were arenas for negotiation, advice and support. It also reveals that there was some sort of charity to support old soldiers in the late 1800s, perhaps a recognition that the Victorian state (as Kipling later observed) was not doing enough.

[from The Morning Post, Monday, October 31, 1870]