Memorial to the Demerara slave rebellion of 1823, which commemorates the Guyanan resistance hero, Quamnina.

I suppose it is too much to ask for consistency from the criminal justice system when cases come in all sorts of shapes and sizes and the circumstances of each can be quite different. This is especially true when it concerns violence, specifically violence which fell under the very broad terms of ‘assault’ in the nineteenth century.

Assault was always a very fluid term in law, made clear in instructions to magistrates from Dalton to Burn from the 17th to the early 19th century. Even the advent a professional police and the creation of a Police Code book did little to cement a clear understanding of what assault really was. By the later 1800s there was at least distinction between ‘common’ and ‘aggravated’ assault, but the former definition was as vague as it had been in the 1700s:

‘A common assault is the beating, or it may be only the striking, or touching of a person’.

Police were advised not to arrest aggressors in these cases, ‘but leave the party injured to summons’ them. If actual violence was evident (wounds were obvious for example) the officer was obliged to take culprits into custody, even if they hadn’t seen the incident themselves.1

This allowed a lot of leeway and makes it quite hard for us, as historians, to compare assault cases. When we add to this the fact that most – almost all in reality – were prosecuted before the magistracy (where records are scant at best) we are at a severe disadvantage in understanding the contexts and causes of non-fatal violence in history. It makes it equally difficult to understand why some cases resulted in fines and others led to long prison sentences. It isn’t always as simple as looking at the level of violence used, as this pair of cases from 1843 illustrate.

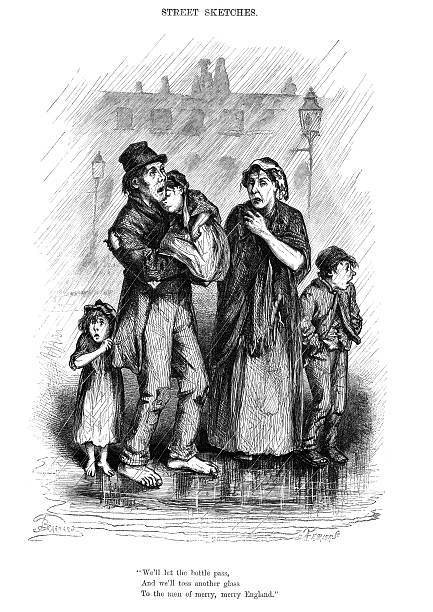

Violence was often associated with drunkenness, and this took many forms. Mary Denyer was strolling along the Mile End Road, minding her own business one afternoon, when two young men approached her.

Thomas Webb and George Todd had been drinking, enjoying a holiday from work. They grabbed hold of Mary and ‘twirled her abou, but rather too vigourously. Perhaps this was ‘high jinks’, or two boorish young men behaving badly towards a vulnerable female that happened to cross their path.

Regardless of their motives – sinister, or simply crass and stupid – the young tailoress was pregnant and the shock and rough handling she received by being ‘twirled about’ caused her to faint to the pavement.

The men quickly ran off instead of helping her, not the best idea under the circumstances because they’d been seen by a policeman. The officer, having left Mary in the care of a passerby, set off in pursuit. The pals were quickly captured and when brought before the Thames magistrate, were very apologetic, but said they were only having ‘a lark’. They were drunk, they’d seen a pretty girl and they’d had a dance with her. They didn’t intend to hurt her, and they had no idea she was with child.

None of this cut much ice with the magistrate, Mr Broderip. He condemned their behaviour and said they had committed a ‘gross outrage’ on the poor girl. As a result he fined them £5 each, money he almost certainly knew they didn’t have. That condemned them to spend the next two months in prison.

I’ve no defence for Todd and Webb, they acted very badly and deserved punishment. But I am interested in justice Broderip’s seemingly inconsistent treatment of assault in his courtroom.

Broderip’s fury at the action of two ‘ruffians’ towards a pregnant women was not matched by his reaction to an assault on a sailor who complained at his court the following day.

Joseph Beale has signed up as an ordinary seaman on the Ludlow a merchant vessel sailing from Demerara (modern day Guyana) to London. On more than one occasion the captain, William Johnson, had abused Beale and accused him of failing to do his job properly.

There were two key incidents that Beale accused his master of:

beating him with a stick and punching him and smashing him in the face with a ‘spitting-box’ (a spittoon).

The violence he’d suffered was, by his own account, severe and certainly aggravated. It was also deliberate, related and sustained. Beale told Mr Broderip he had been struck more than a dozen times with a stick. Had he counted the blows he’d received the magistrate asked him Yes, the sailor replied, he had, or at least until he reached 12 when he stopped counting.

The captain was defended in court by Mr Price, a barrister who cross examined Beale and discovered that the captain had also lowered his wages, on the grounds that he was only a ‘ordinary’ season not an ‘able’ one (as Beale had apparently claimed).

Beale said he’d never claimed any such thing but perhaps the damage was done and it certainly convinced the magistrate that the man was full of resentment towards his superior.

Broderip accepted that an assault had occurred but decided (with no corroborating evidence at all – indeed at least one crew mate corroborated Beale’s account) that Beale was exaggerating it. As a result the magistrate imposed a small fine and advised Captain Jonson to not ‘strike a man in the heat of passion’ in future or get involved in arguments with his crew on deck.

Compare this fine (10s) for actual and severe violence from a person in authority with the (relatively) minor assault that landed two working class men in gaol the day before.

There was another factor here though, Demerera had been a slave colony. In 1823 a rebellion of 10,000 slaves was crushed by the authorities and many of those accused of involvement were hanged. The revolt probably helped finally undermine slavery and the callous treatment of those involved and the horrors it exposed it undoubtedly ruled the abolition movement. In 1834 slavey was officially abolished in Demerera (under the terms of the 1834 abolition act), so just 9 years before this incident reached Broderip’s court.

We might note that while slavery was an abomination in many people’s eyes parliament still saw fit to compensate the plantain owners for the loss of their ‘property’. In Demerara this amounted to £4,297,117 10s. 6½d (or close to £300m in today’s money).

Joseph Beale was ‘a man of colour’, and so maybe one of those freed in 1843, or the son of freed slaves at least. So just perhaps, in the eyes of Mr Broderip, he was not worthy of more ‘justice’ in his courtroom, especially not when the subject of his complaint was a white man in a position of authority.

[From Morning Post, Wednesday 11 January 1843; The Standard, Thursday 12 January 1843]

- Sir Howard Vincent’s Police Code 1889 edited by Neil R A Bell and Adam Wood, (Mango Books, 2015), p. 25

Drew’s latest book, Murder Maps: Crime Scenes Revisited is available from all good bookshops (if you can find one open!) and online via various outlets: e.g Waterstones and Amazon