In these days of contactless payments and Oyster cards it’s easy to forget that not so long ago one used to need a ticket to travel on London transport. I remember bus conductors with their machines spewing out paper tickets like the waiting systems in some supermarkets and surgeries, and we still have travelcards on the tube and trains. But how did our ancestors prove they had paid their fare, were tickets always required, and how were they issued?

When Alfred Pearl appeared at Thames Police court charged with ‘dodging’ his fare to Dalston Junction it revealed the system one tram company deployed to check passengers had paid.

Apparently the North London Tramways Company (NLTC) didn’t trust its their own employees. It had adopted a system whereby none of its conductors could collect fares from those boarding their trams. Instead a ‘collector mounts the car and collects the fare, giving to each passenger a ticket, which is to be delivered up on leaving the car’.

So you got on, waited until a collector got on, then paid him, and carried on your journey clutching your ticket. As long as you had one you were ok; fail to produce it however and you’d be asked to cough up. This seems very like the system of inspectors we have now. They may be infrequent visitors to the buses and trains of the capital but I’ve been asked for my ticket (or my contactless debit card) a number of times in the past 12 months.

Alfred Pearl had boarded a tram car at somewhere before Kingsland Road on a Saturday afternoon in August 1873. At Kingsland Road Philip Egerton, one of the company’s collectors, ‘demanded his fare in the ordinary way’ but Pearl refused him. He said would not pay his fare in advance, but only once he had reached his destination.

I suppose this is a reasonable position to hold given the unreliability of transport systems now and then. After all most people paid for services they had received, not that they were about to receive. Pearl said he was going to Dalston Junction and would pay his fare there, and so the tramcar carried on. At the Junction however Pearl now insisted he wanted to continue his journey further, and remained adamant that he would only pay on arrival.

The collector asked him for his name and address, and when Pearl refused to give them Egerton called over a policeman and asked him to arrest the man. The policeman was not inclined to waste his time but Pearl decided he was going to clear his name, and make a point, so he took himself to the nearest police station where he again refused to pay or give his name. The desk sergeant had him locked up and brought before a magistrate in the morning.

In front of Mr Bushby at Thames Police court Alfred insisted he had done nothing wrong. He ‘denied the right of the [tram] company to demand or receive his fare before he had completed his journey’. In response the NTLC’s solicitor Mr Vann ‘produced the by-laws of the company’, which clearly demonstrated (at section nine) that they were perfectly entitled to do just that.

Mr Bushby wasn’t clear how to proceed. He wasn’t aware of whether the company’s own by-law was valid and he would need time to seek advice and consider the legal implications of it. For the time being he adjourned the case and released the prisoner who went off loudly complaining about being locked up in the first place. Mr Pearl was no ordinary traveller either, he was smartly dressed and may have been ‘a gentleman’. It seems he was quite keen to test the law but hadn’t bargained on being held overnight as an unwilling guest of Her Majesty.

The case came back to court in October 1873 where the tram company were represented by a barrister as was the defendant. Astonishingly here it was revealed that Pearl had actually offered the policeman 10sto arrest him and the collector (Egerton) a whole sovereign if he would prosecute. It was claimed he declared he ‘would not mind spending £100 to try the matter’.

This then was a clear case of principle to Mr Pearl.

His lawyer (Mr Wontner) cross-examining the ticket collector ascertained that Pearl’s defence was that when he had been asked to pay had explained that he had refused because:

‘his mother had on the previous day lost the ticket given on payment being made, and had been compelled to pay again’. He had told the collector in August that his own ticket had ‘blown away in a gust of wind’.

Evidently Pearl was not the usual fare dodger (and there were plenty of those brought before the metropolitan police courts) and Mr Bushby had no desire to punish him as such. He (the magistrate) also felt the circumstances of the arrest and imprisonment had been unjustified and so agreed Mr Pearl had been treated poorly. The by-law however, was ‘a very excellent regulation’ but ‘it was informal, and consequently not to be enforced’. The whole matter was, he was told, to go before the Queen’s Bench court for consideration so there was little for him to do but discharge Mr Pearl without a stain on his character.

Thus, the man on the Dalston tramcar (if not the Clapham omnibus) had won a small victory, but I doubt he won the argument in the end as we are well used to paying up front for a journey that might be uncomfortable, delayed, or indeed never reach the destination we ‘paid’ for.

[from Reynolds’s Newspaper , Sunday, August 24, 1873;The Morning Post , Saturday, October 04, 1873]

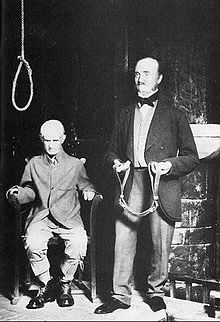

Perhaps likening himself to the infamous Charlie Peace – the self-styled ‘king of the lags’ – Terroad claimed to have committed over 120 burglaries in London in his short career. Given he was only 23 years of age in 1888 this was some résumé, but on this occasion he’d been caught.

Perhaps likening himself to the infamous Charlie Peace – the self-styled ‘king of the lags’ – Terroad claimed to have committed over 120 burglaries in London in his short career. Given he was only 23 years of age in 1888 this was some résumé, but on this occasion he’d been caught.