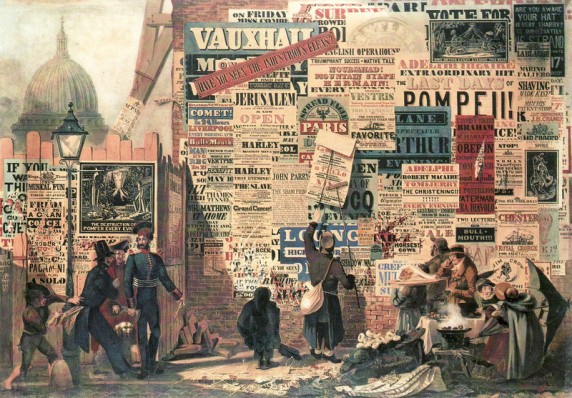

John Tenniel’s Nemesis of Neglect, Punch (29/9/1888)

On Friday 31 August 1888 the Standard newspaper reported on the ‘great fire’ that had raged at the London docks the night before. Workers had knocked off at 4 that day as usual but at 8.30 in the evening someone noticed the smell of burning. It took until nine for the authorities at Whitechapel to be alerted whereupon officials there ‘ordered every steamer to proceed to the scene’. By the time they got there (coming from all over the city) a massive fire was underway.

The fire was raging in the South Quay warehouses which were ‘crammed with colonial produce in the upper floors and brandy and gin’ at ground floor level. With so many combustibles it is not surprising that the 150 yard long building blazed so violently. The conflagration not only drew the police and fire brigade to the site it also attracted thousands on Londoners in the East End to step out of their homes to see the fire.

The Pall Mall Gazette also featured a report on the fire within its fourth edition that day. It described the warehouse as 200 yards long and said 12 steamers were engaged in fighting the blaze. It reported that soon after the first fire was brought under control a second broke out at the premises of Messrs. J. T. Gibbs and Co. at the dry dock at Ratcliffe, damaging workshops, goods and a nearby sailing ship, the Cornucopia.

As dramatic as the dockyard fires were they were eclipsed by an adjacent report on the same page which read:

HORRIBLE MURDER IN EAST LONDON

ANOTHER WHITECHAPEL MYSTERY

This of course refereed to the gruesome discovery made by police constable John Neil as he walked his beat along Buck’s Row (now Durward Street) parallel to the Whitechapel High Street. PC Neil had found the dead body of a woman later to identified as Mary Ann ‘Polly’ Nichols, the first ‘canonical’ victim of murderer known to history as ‘Jack the Ripper’.

The Gazette’s reporter must have seen the body in the Whitechapel mortuary because he was able to describe it in some detail for his readers.

‘As the corpse lies in the mortuary it presents a ghastly sight […] The hands are bruised, and bear evidence of having been engaged in a severe struggle. There is the impression of a ring having been forced from one of the deceased’s fingers, but there is nothing to show that it had been wrenched from her in a struggle’, ruling out (it would seem) robbery as a motive.

No one, it seems, had heard anything despite there being a night watchmen living in the street. It was a mystery and as more details of Polly’s injuries emerged in subsequent days the full horror of the killing and the idea that a brutal maniac was at work in the East End gained ground in the press.

Meanwhile it was business as usual for the capital’s Police Courts; at Thames Francis Greenfield was charged with cruelty to a pony. He was brought in by PC 73K who had found the man beating the animal as he exercised it around a circle, presumably training it. The poor ‘animal was bleeding from the mouth, and there was a wound on the side of its lip’. The constable was told by several bystanders that Greenfield had been ‘exercising’ the beast for well over an hour. Mr Lushington, the magistrate, adjourned the business of his court to go and see the pony for himself. When he returned he sentenced Greenfield to 10 days imprisonment with hard labour for the abuse.

Having dealt with that case the next reported one was of Philip McMahon who was in court for beating his partner, Emily Martin. The pair had been cohabiting for four or five years and it wasn’t the first time he had hit her. After a previous incident, when he’d blacked her eye, she had forgiven him and had done so several times since. Then on Monday (27 August) he had come up to her on the Mile End Road and grabbed her by the throat. He tore off a locket that she wore and assaulted her. He declared he was leaving her and when she tried to reason with him and implore him not to go he hit her again, knocking her senseless. Mr Lushington gave him 6 months hard labour.

Both cases testify to the violence and cruelty that was often associated with the working class residents of the East End of London. This allowed the press to construct a picture of Whitechapel as a place that had abandoned any semblance of decency. The area became the ‘abyss’, a netherworld or living hell, where life was cheap and personal and physical corruption endemic. The “ripper’ became the embodiment of this vice and crime-ridden part of the Empire, given form by John Tenniel’s nemesis of Neglect, published on 29 September 1888 at the height of the murder panic. As with the modern press, historians and other readers need to be very careful before they take everything written in them at face value.

[from The Standard , Friday, August 31, 1888; The Morning Post, Friday, August 31, 1888;The Pall Mall Gazette , Friday, August 31, 1888]

for more Ripper related posts see:

Cruelty to cat grabs the attention of the press while across London the ‘Ripper’ murders begin.

“Let me see the Queen, I know who the ‘Ripper’ is!”