We are familiar with the idea of gentleman dueling over some slight to one or the other’s honour and there were some very famous protagonists in the nineteenth century. The Duke of Wellington fought a duel (in secret – by then the practice was at best severely frowned upon ) with the Earl of Winchelsea. While the elites of Europe had resorted to swords and then pistols to settle their differences in the 17th and 18th centuries, by the 1800s most chose to pursue their opponents for libel in the civil courts. The practice was increasingly reserved for military men and became less and less ‘respectable’.

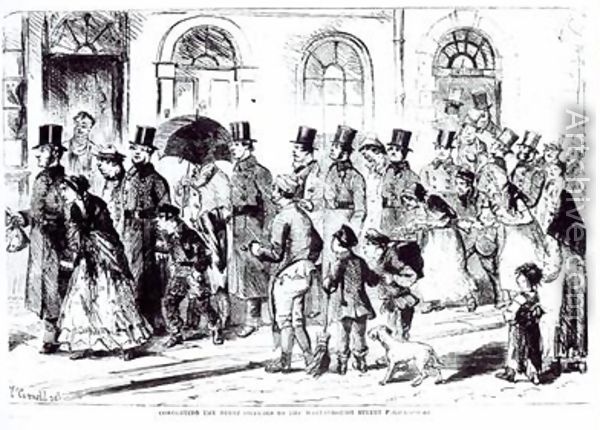

The Duke of wellington fights a duel

The authorities did prosecute duelists in the early 1800s as two cases from the newspapers in July 1808 show. A pair of officers from Bow Street (Adkins and Rivett) received information that two foreigners, Sandoz (a jeweler) and Dubois (a journeyman watch-case maker) were planning to fight a duel at Chalk Farm the following morning. The Runners set off for Chalk Farm early on the next morning but Sandoz and Duboius didn’t show up.

It was later established that they had been tipped off that the officers were after them and their friends persuaded them to ‘shake hands’ on their dispute. Sandoz was taken before the Bow Street magistrate who bailed him to keep the peace towards Dubois.

Meanwhile another case was presented before the justice at Bow Street. This time a letter was given to one of the Bow Street Runner, Mr Lavender, by a landlord in Wardour Street, London. The letter was supposedly written by a tailor named William MacIntosh and was addressed to an attorney’s clerk named McCreary.

It said:

‘Mr. Mac Craery, you are to come to chalk farm tomorrowe mourning at hafe past six clock, and hare to harm yourselfe with what-ever you pleaise acept a sworde’

“Wm. Macintosh”.

Lavender went to Chalk Farm but again he found neither man there so called on them both in turn. MacKintosh claimed he had turned up an hour too early and went away again. McCreary said he hadn’t been given the note until after the time at which point he had himself gone to the Bow Street office to complain about the tailor’s threats.

The letter (which I have transcribed just as it was written in the paper, complete with poor spelling) was not in Mackintosh’s handwriting (which initially confused McCreary as he didn’t recognize it). This was explained in court when it was revealed that the landlord’s nine year old son had penned it on behalf of the tailor.

The two men made up their differences and so there was no need for the magistrate to do any more than presumably warn them that this was not a legal nor a sensible way to settle their arguments.

Why choose Chalk Farm? In the eighteenth century and early 1800s it was ‘it was particularly suitable for the purpose, as it was near town, and at the same time quite secluded’, as one history tells us.

[from The Examiner, Sunday, July 31, 1808]