Billingsgate Marketing the morning by Gustave Doré, 1872

Drunkenness is usually associated with this time of year. People have plenty of time off work and numerous social occasions in which drink plays an important role. Whether it is sherry before Christmas dinner, beer on Boxing Day in the pub, or champagne and whiskey on New Year’s Eve, the season tends to lead some to imbibe excessively.

Not surprisingly then the Victorian police courts were kept busier than usual with a procession of drunkards, brawlers, and wife beaters, all brought low by their love of alcohol. Most of the attention of the magistracy was focused on the working classes, where alcohol was seen as a curse.

By the 1890s the Temperance Movement had become a regular feature at these courts of summary justice, usually embodied in the person of the Police Court Missionaries. These missionaries offered support for those brought before the ‘beak’ in return for their pledge to abstain from the ‘demon drink’ in the future. These were the forerunners of the probation service which came into existence in 1907.

In 1898 Lucas Atterby had been enjoying several too many beers in the Birkbeck Tavern on the Archway Road, Highgate. As closing time approached he and his friends were dancing and singing and generally making merry but the landlord had a duty to close up in accordance with the licensing laws of the day. Closing time was 11 o’clock at night (10 on Sundays) but Atterby, a respectable solicitor’s clerk, was in mood to end the party. So when Mr Cornick, the pub’s landlord, called time he refused to leave.

Mrs Cornick tried to gentle remonstrate with him and his mates but got only abuse and worse for her trouble. The clerk leered at her and declared: ‘You look hungry’, before slapping her around the face with ‘a kippered herring’ that he’d presumably bought to serve as his supper or breakfast.

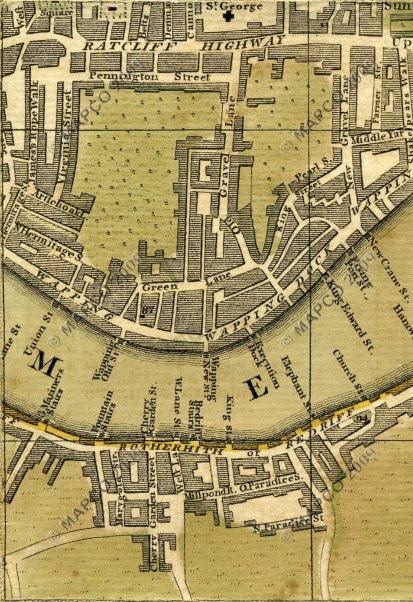

It was an ungallant attack if only a minor one but if was enough to land Atterby in court before Mr Glover at Highgate Police court. The magistrate saw it for what it was, a drunken episode like so many at that time of year. He dismissed the accusation of assault with ‘a Billingsgate pheasant’ (as kippers – red herrings – were apparently called) but imposed a fine of 10splus costs for refusing to quit licensed premises.

The clerk would probably have been embarrassed by his appearance in court (and the pages of the Illustrated Police News) and if he wasn’t he could be sure his employer would have been less than impressed. It was a lesson to others to show some restraint and to know when to stop. A lesson we all might do well to remember as we raise a glass or three this evening.

A very happy (and safe) New Year’s Eve to you all. Cheers!

[from The Illustrated Police News, Saturday, 31 December, 1898]