In 1888 the comedian Walter Groves appeared, not on stage this time, but in the dock at Worship Street Police court. He had been summoned by his former manager and fellow comedian Henry Bruce who accused him of assaulting him after the pair had fallen out in a dispute over what we would probably term ‘intellectual property’.

Back in February 1888 Bruce had employed Groves to perform as part of his theatre company. The comedian had written (or perhaps co-written) a sketch act that brought the house down on Easter Monday. On the basis of that success they decided to carry on performing the act and, Bruce insisted in court, had agreed to share the proceeds.

As seems so often to be the case in show business however, the pair fell out and eventually Bruce was forced to let Groves go but seemingly carried on using his material. This clearly irked the other man and on 14 May that year Groves found his former collaborator deep in conversation with the manager of the Forester’s Music hall (also known locally as Lusby’s after its owner, William Lusby). He strode up to the seated pair and loudly accused Bruce of stealing his idea and denying him the profits of it.

The court was shown evidence of playbills listing some of the sketches performed by ‘Harry Bruce’s Company of Comedians’ such as: ‘A sweep for king’ and ‘the Tin Soldier’ that Groves presumably claimed were originally his. It also heard that when Bruce denied any wrongdoing and insisted Groves leave the comedian challenged him to step outside and fight him, man to man. When the other man declined this invitation to a fist fight Groves thumped him in the face and gave him a black eye.

This was corroborated by Frederick Clarence, a comedian in Bruce’s troupe, and by Charles Barber who worked for Bruce as clerk. In defence of Groves Neal Dryden (himself a comic) said his friend was sorely provoked, adding that he understood that Mr Lusby had wanted to employ Groves to perform in the act but Bruce had told him not to, saying the other man was ‘no good’. So with his character and talents impugned and his creative ideas ‘stolen’ from him it was hardly a surprise that Groves lashed out. It didn’t convince the magistrate however who ordered the comedian to find two sureties of £25 each to ensure that he kept the peace towards Bruce for the next twelve months at least.

William Lusby was a minor local celebrity in the 1880s and his first music hall was a popular venue on the Mile End Road. He had taken over the premises in 1868 and rebuilt the theatre, reopening it in April 1877 as Lusby’s Summer and Winter Palace. When it opened a gushing press review stated:

‘This new place of amusement, which, both on account of its great size and the splendid appearance of its interior, deserves to be described as “grand,” was opened to the public for the first time on Easter Monday evening. It affords accommodation for five thousand visitors, and there must have been nearly that number of persons who availed themselves of the earliest opportunity to see the magnificent building which Mr William Lusby has had erected for the use of the pleasure-seekers of the Mile End-road and its vicinity, as well as to witness the performances of the large and talented company of artistes which he has engaged’.

(The Era, 8 April 1877)

However, by 1888 Lusby had sold the theatre and it later burned down in a fire in 1884. A new music hall rose from the ashes, the Paragon which opened in 1885 but by then Lusby had moved on, opening the Forester’s Music Hall where Bruce and his fellow comedians performed their sketch act.

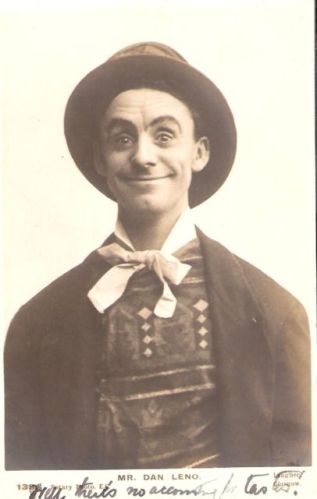

Lusby, an East End lad made good, had built his success on property speculation and had, he claimed, only got into show business to help a young relative get a foot on the ladder. The Foresters was on Cambridge Road East, in Bethnal Green and in 1885 it gave Dan Leno his first big break in the entertainment industry. The legendary music hall star performed two comic songs and a clog dance and was paid £5 a week for doing so. Leno is credited with inventing stand up comedy which is probably why his name is still remembered today while Harry Bruce and Walter Groves have disappeared from history.

[from The Standard, Wednesday, May 31, 1888]

If you enjoy this blog series you might be interested in Drew’s jointly authored study of the Whitechapel (or ‘Jack the Ripper’) murders that is published by Amberley Books on 15 June this year. You can find details here: