This is one of those unremarkable cases, which, at the same time, serves to illustrate how the police courts of Victorian London actually operated. Most of the time the press does not discuss the various functions of the court. Partly this was because it is unlikely that the reading public were interested but also presumably because most people knew anyway. After all these were popular arenas for negotiating social issues and held few secrets for most of the people of Victoria’s capital.

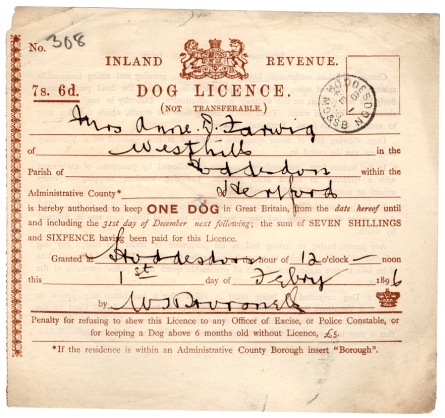

On Thursday 24 June 1880 a number of people were brought to the Worship Street Police court charged with keeping dogs without paying for license to do so. We might have forgotten but until 1987 anyone owning a dog had to buy an annual license. In 1880 this cost 7s 6d (equivalent to about £25 today) so while not a huge sum it was still a cost on the stretched income of the workingman. So it is not surprising that large numbers of people tried to avoid it.

This meant that periodically the capital’s police courts were filled with defaulters, most of whom were expected to pay up on the spot or face a possible fine and/or imprisonment if they couldn’t pay. Being sent to gaol for not having a dog license was not impossible but it was extremely unlikely.

On this occasion one man seemed keen to pay what he owed but then get out of court quickly and without drawing attention to the fact that he’d been there. This was understandable; no one wants his neighbours to know that he has been in court or in trouble with the law, it was potentially embarrassing. So he popped his 5s fine on the ledge of the dock and tried to leave by the main entrance. A warrant officer stopped him and told him he had to go out by the door marked ‘prisoners’, which he was reluctant to do.

When the fellow refused point blank the officer picked up his coins and shoved the man towards the exit door. However, the poor man clung to the dock and continued to refuse to be expelled via the prisoners’ exit. Two more officers arrived, and a police sergeant, and a struggle ensured which ended in an unseemly wrestling match on the court floor.

Finally the man was dragged out of court by his collar and thrown into the street. If he wanted to avoid attention he’d failed quite spectacularly but it was the behaviour of the police and court officers that upset Mr Bushby, the presiding magistrate.

In the afternoon he called the sergeant and officers before him and upbraided them. He told them that they had exceeded their authority and had shown too much ‘zeal’. Given the minor nature of the man’s offence there was no need for rough stuff. He was not supposed to leave his money on the ledge nor was the warrant officers supposed to pick it up from there. They should have told him to pay it to the ‘proper officer’ and, had he refused, they were required to let him leave. There was no requirement that he be imprisoned in default of payment and the proper procedure was for a distress warrant to have been issued if he continued to default on payment.

The man had been injured in the kerfuffle and Mr Bushby wanted it made clear to the officers that he didn’t want to see that sort of incident in his courtroom ever again, and he wrote a letter to the police inspector for K Division to place that on record.

So this uninteresting case becomes interesting (to me at least) because it shows how the courts operated when a fine was due to be paid. It also reveals that there was an exit designated for prisoners (or anyone presumably who had been charged, regardless of whether they came in from the street or from the cells). These were multi-purpose courts; they didn’t simply deal with ‘crime’ and we can all appreciate that some of those that found themselves there were hardly ‘criminals’ by any measure of that term. So making them walk out of a door marked ‘prisoners’ was probably likely to upset those that felt they had done little to deserve the blemish on their character.

[from The Standard, Friday, June 25, 1880]