A little after 1 in the morning on the 27 May 1889 Dr Edward Cooney was called to a house in Bayonne Road, Fulham. His patient was a woman in her early forties, who was unconscious and who appeared, to Cooney, to be suffering ‘from compression of the brain’. On examining her he found a bruise on the side of her face, by the left ear, and one under her eye.

Turning to the woman’s husband (Charles Mills) he asked how she had come by the injuries, and he admitted inflicting them himself. He treated Mary Jane Mills and left her in the care of her husband and son. Within two days however, she was dead, never recovering from her condition.

In due course Charles Mills was arrested and charged at Hammersmith Police Court with causing her death.

In court Mills again admitted hitting his wife but said it was in response to her attacking him in the middle of the night. According to his account he had been woken by her striking him hard across his head. Half-asleep he had retaliated and presumably thought he had done enough to send her back to sleep. He only realised that he had done her more harm when he awoke in the middle of the night.

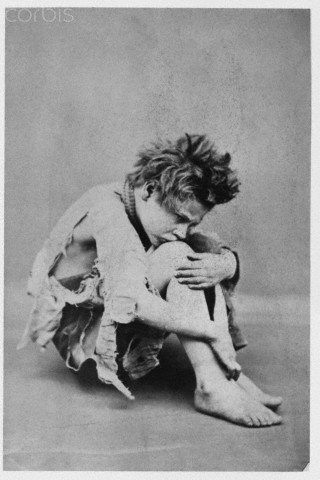

Mary Jane had a history of drinking and was seemingly unable to cope with life. The couple’s son lived with them and later testified to his mother’s erratic behaviour and inability to keep the house clean and tidy. Charles Mills was a bookseller, and his son worked as a fishmonger; they had respectable occupation even if they do not seem to have been particularly well-off. Mary Jane was not fulfilling her allotted role in life, as help-mate and mother. This probably counted against her in the view of society.

On May 30th 1889 Charles Mills was remanded in custody by Mr Hannay, the Hammersmith magistrature, and on 24 June of that year he was formally tried before jury at the Old Bailey. The charge was manslaughter and the court heard that Mills was a well respected man with a good character. His wife’s drinking was detailed in court and so was evidence that this was not the first time Charles had hit her.

A neighbour told the Old Bailey court that she had witnessed or heard several alterations between them in recent weeks, including threats to her life:

‘I remember one occasion’, Hannah Noble recounted, ‘ about four weeks previous to this occurrence—about twelve o’clock, after he came home from his work, he gave her a thrashing—I saw it through their window, which had no blind, and I saw her next day with a pair of black eyes and scratches on the side of her face—on one occasion, towards twelve o’clock, I heard him say he would do for her.’

Whether Charles Mill meant to kill his wife or not is impossible to say, but men routinely used violence in the 1800s towards their spouses and children. Domestic murder was not at all uncommon and the most likely context in which homicide occurred. While the Whitechapel murders of Jack the Ripper dominated the news hole in the 1880s incidents like this were far more typical of the daily tragedies that befell women in late Victorian London.

The jury found Charles guilty of manslaughter; how could they not given his confession to the police, his son, and Mary Jane’s mother in the immediate aftermath of her death? But they recommended him to mercy on ‘account of his character and the great provocation he received’.

The judge sentenced him to 12 months impriosnment at hard labour.

[from The Standard , Thursday, May 31, 1889]