In yesterday’s post I discussed the casual racism and anti-Semitism that was endemic in late nineteenth-century London and led to the passing of the Aliens Act in 1905 (the first legislation aimed at controlling immigration). Throughout the 1800s Britain was a beacon of hope for refugees from persecution on political, religious or other grounds. It was also in Britain that the campaign to abolish slavery had found its political leadership.

Of course England and Britain more broadly had arguably profited most from the use of slave labour and the ‘triangular trade’. The passing of the Slave Trade Act in 1807 abolished slavery in all British Colonies, but compensated slave owners heavily. It was an important first step.

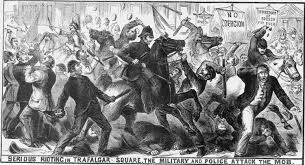

In the 1860s slavery still existed in the USA and in 1861 war broke out in America, in part as a result of efforts to abolish the practice. A year after England had abolished the trade in African slaves the US passed a law to prevent importation of slaves to America, but this did not free those slaves already working on (mostly) southern plantations. In fact Northern owners simply started to sell their slaves to southerners. Gradually a situation emerged (made law after 1820) that divided America into southern slave owning and northern ‘free’ states.

In 1860 Abraham Lincoln was elected President of the USA, the 16th to hold that office. A Republican and a dedicated abolitionist, Lincoln did not win a single southern state. A month later South Carolina seceded (left) from the Union and cited Northern ‘hostility to slavery’ as a reason for doing so. Between January and February 1861 Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana and Texas followed and the Confederacy was born.

War followed in April that year with the attack on Fort Sumpter and it raged until the south was finally surrendered at Appomattox courthouse on 9 April 1865. Slavery was finally abolished in all US states by the 13thAmendment to the constitution, passed on 18 December 1865. By that time its key champion, Lincoln, was dead, shot in Washington by John Wilkes Booth.

Britain watched the Civil war with interest. America was slowly becoming a rival economic power and British merchants continued to trade with the south after secession. But anti-slavery was also now written into the English legislature and voices here supported the North in its ambition to end the inhuman practice once and for all.

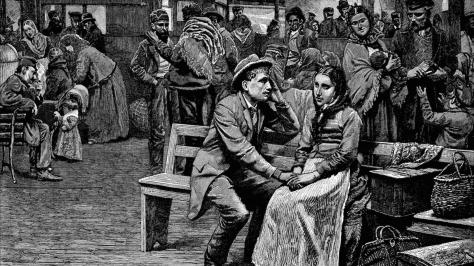

In July 1863 as war continued across the Atlantic a former slave appeared in court at Bow Street. George Washington was a young black man that had arrived in London with his father, fleeing from the war and slavery. He was in court because he’d been arrested whilst begging in Whitehall. He was stood in the street with a placard around his neck that explained his fate and aimed to draw sympathy from passersby.

He was having some success it seems because PC William Waddrupp noticed that a crowd had gathered around him and were placing money in his cap. Begging was illegal and so he took him into custody.

At Bow Street it emerged that Washington and his father had found lodgings with a costermonger in Mint Street, in the Borough. The coster had arranged for the placard to be printed and ‘managed’ the ‘appeal’ for funds. Whether he did so out of the goodness of his heart or because he saw an opportunity to take a slice of the income is a question we’ll have to keep hanging in the air. He wasn’t prosecuted for anything at Bow Street anyway.

Mr Hall was keen to hear how George and his father had come to be in London. Mr Washington senior said that he had been a drummer in the Confederate army and that his son had been servant to ‘one of the rebel captains’. In the aftermath of the battle of Bull Run (probably the first one in July 1861) they escaped and ran to the north making their way to New York.

They hoped to find a sympathetic ear and help but got neither until they met a man named General Morgan. He told them to go to England ‘where they had a great affection for slaves, and would no doubt provide for them comfortably’. Working their passage they found a ship and landed in London at some point in 1863. There they met the costermonger and he suggested the strategy of asking for alms in public. They had no idea it was against the law to beg in England and said they would be happy to return to New York if a ship could be found to take them under the same terms as they had arrived.

Mr Hall was minded to believe them. They were in breach of the law but he accepted that they had been badly advised (here and by General Morgan) so he discharged them. I wonder if by highlighting their plight they might have got someone to help them – either to return to the US or to stay and prosper in London.

There was sympathy and no obvious racism on show at Bow Street (in stark contrast to Mr Williams’ comments on Jews appearing at Worship Street nearly 30 years later. This is possibly explained by the relative lack of black faces in 1860s London. Black people were a curiosity and not a threat in the way waves of Eastern European immigrants were seen in the 1880s. Moreover the politics of anti-slavery were still very strong in London at mid century and while some merchants and sections of government might have had economic or geopolitical reasons for supporting the Confederacy there was widespread sympathy for the plight of the slaves.

For these reasons , and perhaps simply for the fact that George Washington and his father had entertained Mr Hall and his court with a fascinating story of courage and ‘derring-do’, they won their freedom all over again.

[from The Morning Post, Tuesday, July 31, 1863]