An incident in the Revolutionary War of America (The Fraser Highlanders at Stone Ferry) – Robert Ronald McIan (1854)

Robert McIan probably thought he was doing someone else and himself a good turn when he ‘rescued’ John Coster from his perilous condition on the streets of central London. It was the dawn of the Victorian age – 1837 – and the comedian and artist was strolling near his home on Newman Street, off Oxford Street, he saw a man in ‘a wretched state of constitution and starvation’. He decided to take him home and feed him.

McIan would later admit that his motivation was more than just that of a good Samaritan; he recognized that Coster’s ‘picturesque appearance’ made him a perfect subject for artist study. Coster was an Indian from the Bengal, who had been born a ‘Mohametan’ but had converted to Catholicism. He spoke English, but with a heavy Indian accent.

He was treated with some compassion by McIan who made him a servant in his household but he was also a ‘curiosity’ and was shown to the artist’s friends, several of whom painted him themselves. Coster then was drawn and painted by no lesser figures than ‘Sir David Wilkie, Landseer, Etty, Ewins, and most of the celebrated painters of the day’.

In McIan’s head he had done the man a great service so it must have come a terrible betrayal of trust to discover that the man he had saved from the streets had robbed him. Yet in March 1840 that is exactly what he alleged. A pistol had disappeared from his painting room and, since Coster (who had also vanished) was familiar with the room and its contents, and the door had been forced open, suspicion fell on him.

A description of the missing servant and the gun – a ‘Highland pistol’ – were circulated and several months later both were recovered. The pistol had been pawned on Tottenham Court Road and it was easy to trace that back to Coster given his distinctive appearance as an Asian in London.

At his appearance at Hatton Garden Police court Coster was also accused of a second robbery. Since he’d quit McIan’s service he had been living in lodgings St Giles and his landlady deposed that he had plundered her rooms before running out on her as well. Coster admitted stealing the pistol but vehemently denied any knowledge of the other charge.

Mr Combe, the sitting magistrate that day, told Coster he would be remanded in custody while further enquiries were made and other witnesses sought. But he informed the prisoner that if he was convicted all of his luxurious long black hair would be shaved off.

‘No!’, Coster exclaimed from the dock, ‘da neber sall; me die first before da sal cut de hair off’.

Robert Ronald McIan (1802-1856) was a popular artist in the Victorian period known for his romanticized depictions of Highland life and history. He had trod the boards in the theatre in his youth (which may explain why he still described himself as a ‘comedian’ in 1840). He is most well known for his “Battle of Culloden’ and ‘A Highland Feud’ (both 1843) and in the same year he exhibited ‘An Encounter in Upper Canada’ which depicted the heroic fight between Clan Fraser and a larger French and American Indian force. The Highland pistol that Coster probably featured in some of these paintings and, who knows, maybe his former servant did as well in some way.

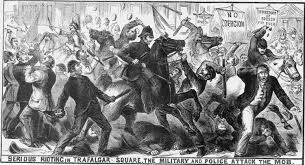

Edwin Landseer (1802-1873) also had his Scottish connections – his ‘Monarch of the Glen’ (1851) is one of the most famous images of nineteenth century art. In 1858 he was commissioned to create the four bronze lions that guard Nelson’s Column in Trafalgar Square.

Sir David Wilkie (1785-1841) was, famous for his historical paintings. Like McIan he was a Scot, born in Fife the son of a clergyman. Soon after the court case that involved Coster and his acquaintance McIan he travelled abroad, painting the portrait of the Sultan in Constantinople and various others on including Mehemet Ali in Alexandria, Egypt. He fell ill at Malta and died on the return voyage.

As for John Coster I’m afraid history doesn’t record what happened to him. There’s no record of a jury trial for this theft of an artist’s pistol or the robbery of a St Giles lodging house. Once again, the mysterious Indian with the ‘long black hair and dark piercing eyes’ vanished.

Above right: ‘General Sir David Baird Discovering the Body of Sultan Tippoo Sahib after having Captured Seringapatam, on the 4th May, 1799,’ by Sir David Wilkie (1839) – National Gallery of Scotland

[from The Morning Post, Tuesday 10 March 1840]